Turning to Time: The Temporal History of Cleansing

A few months ago I came across a quote from Fernand Braudel given to Peter Burke on Radio Three in 1977, summarising his Mediterranean research, in terms of relative time:

“My great problem” he said, “the only problem I had to resolve, was to show that time moves at different speeds.”

Twenty years after solving a very similar problem, it seems right to draw attention to temporal methodology, almost exactly 100 yrs after Einstein and Bergson; and 50 years after Braudel’s well-known 1958 essay on the longue duree (on the existence of long, or deep time). Sadly, since that time, historians seem to have fulfilled his prediction, and have been content to leave Time in the small box assigned to it by the physical sciences.

My own methodological problem, as a historian of hygiene, was that all I had to start with was the old Whig positivist history of the onward and upward, linear, ‘March of Hygiene’ – which was already out-dated by the latter half of the 20th century. We were more morally sceptical, and certainly more aware of social structures. How did one account for different geographical standards of hygiene; or the regression of hygiene; or periods of stasis in hygiene? How did one deal with the technology of hygiene? There were many so-called ‘anomalies’ that simply did not ‘fit’ with the accepted story of Progress.

I got my breakthrough (or intuition) via a lone paragraph from Norbert Elias in ‘Court Society’ – completely unattributed, in the apparently customary manner of French philosophical historiography – in which he described Time as a flowing river; but, less familiarly, as a river with three speeds: slow biological time, slightly faster social time, and finally, the ephemeral flickering of individual memory. I did not know (yet) that this was a common analogy in late nineteenth-century philosophy. The accompanying text was just enough to build on, however, and I went ahead and ditched several promising theories from various disciplines (cosmological dualism, sociological professionalisation, and economic modernisation) in favour of temporality. It forced me to add roughly 100,000 years onto my original timescale.

Like Braudel – and also of course Norbert Elias – I therefore had to start my book CLEAN with the oldest and slowest layers of time (in defiance of my editors, I may say, who thought this lacked punch). So CLEAN begins with the biological and animal basis of physical bodily cleansing, then adds every succeeding chronological social layer, from ’prehistory’ to the ancient world, through the medieval and early modern, to the present. Biology thus precedes the known ‘archaeology’ and chronology of human techne (products and language), which in turn opens up ‘an orchestra of histories’, each with their own space, matter and time-zones.

In the end Annales time-theory turned out to fit the history of hygiene like a glove. There were no longer any ‘anomalies’, there were simply different types of time, or different levels of time, operating simultaneously. It took full account of the physical dimensions of space and matter. It meant that Nature and Nurture were both complementary and co-existent, and made all ideas of hygienic ‘progress’, or ‘evolution’, or ‘modernisation’, suddenly look like one-dimensional tunnel vision.

[NOTE: THIS SEEMS EVEN MORE TRUE TODAY, WHEN CONSIDERING THE MODERN PLAGUE OF COVID.]

* * * * * * * * * *

If you look carefully, every chronological period can be seen in some shape or form in the contemporary history of hygiene today. I can perhaps describe this ‘simultaneity’ of the temporal process with just one example:

Take a closer look at the bio-social history of your hand. In it’s inner structure (the bits you cannot see, such as the muscles and molecules) it incorporates bio-genetic traits laid down millions of years ago – your hand is ‘species typical’. It also has unique characteristics of genetic ancestry (shape, size, colour); and gender (male or female). It displays unique signs of age, use, and condition; it may also exhibit ancient communal symbols of gender or status (rings, painted decorations, etc); and was only a few minutes ago probably performing a certain trained, habitual and well-known task.

The whole cluster of histories contained in your hand – or indeed any other limb or artefact – shows how one can arrive at a multi-levelled explanation. The Annales effectively saw life as a palimpsest – an accumulation, a storehouse, of histories; and this, ultimately, is what the history of personal hygiene is all about.

We are less commonly aware of different types of time, than we are of linear time. Some time during the second half of the 20th century – in fact only really speeding up at the approach of the millennium – anthropologists, historians and sociologists began to recover the longue duree ‘alternative’ history of human time-use based on subjective human perception. They now talk confidently about diurnal and seasonal time, bodily time, religious time, measured or mechanical clock time, ‘free’ time, task-based time. They have usually discovered that the earlier forms of timing were elastic, often irregular, and wholly relative. Time served specific social purposes, and had specific geographical or spatial locations. (Norbert Elias, Time, an essay written in 1987, published in English posthumously in 1992; Anthony Aveni; Glennie & Thrift)

For the health historian, in fact ‘micro-temporality’ is just as interesting as ‘macro-temporality’. It is particularly important in the organisation of animal and human grooming. Internal body-cleansing (of the evacuations) is a constant process, and the physical functions have their own diurnal pulses and split-second chemical timing. External human grooming is seemingly rhythmic, diurnal, seasonal, calendrical, episodic and task-based, and biologically connected to periods of rest and relaxation, or ‘free-time’ (through the chemical stimulation provided by the sense of touch). In modern temporal terminology, grooming is an integral part of the ‘work-life balance’. These are just some of the ‘structural’, or three-dimensional, temporal routines of personal body-care we will have to be dealing with in the future, probably through oral history; at the moment it is all conjecture.

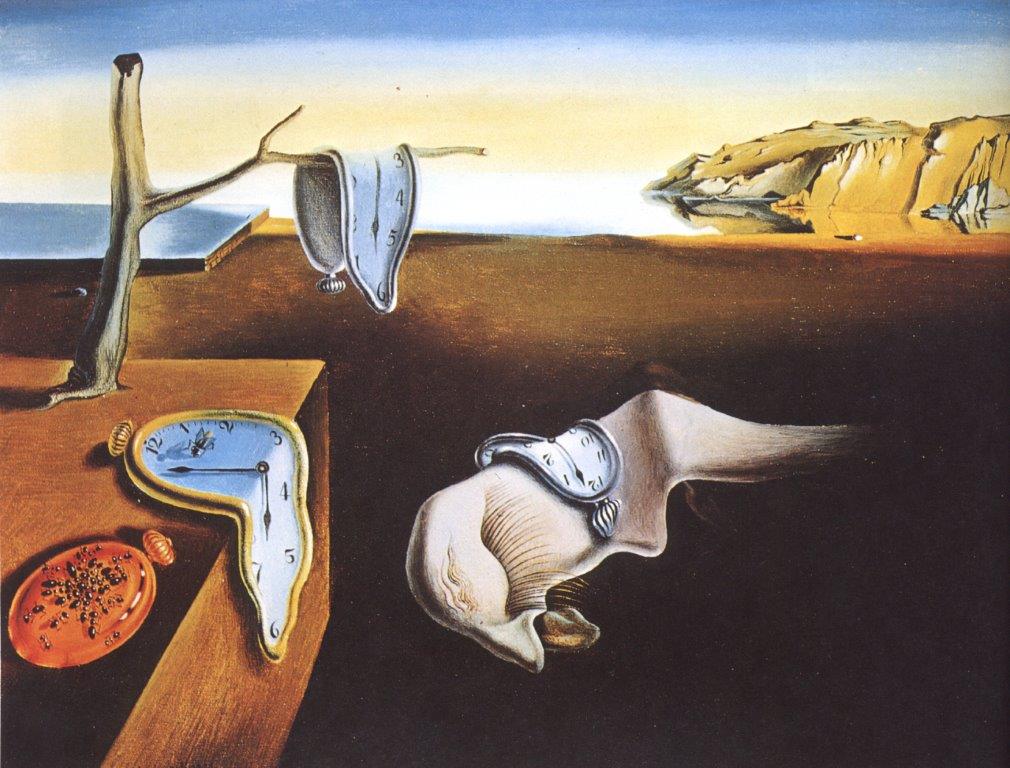

From time to time I would try fruitlessly to track down Elias’s references, and the history of the philosophy of Time became somewhat of an obsession – somewhat like this Dali image (of the exhausted brain!).

In what little time there is left, I will set out a brief narrative of a key episode which arguably we are still living with. I am only looking at one very short duration here; neither can I here follow current scientific philosophy into the deeper problems of three or four-dimensional time (ie. Theodore Sider, Four Dimensionalism. An ontology of persistence and time. OUP. On Minkowski’s spacetime.) Suffice to say, that the philosophical mechanics of multi-dimensional spacetime are still by no means resolved – even though everybody now seems to agree that it exists – and even though it is notoriously ‘counter-intuitive’. I am not sure it matters whether we historians can fathom out ‘A’ series and ‘B’ series, ‘stage views’, or ‘worm solutions’: the essential ideological change has already happened. Dating from the late nineteenth century, European temporal cosmology subtly and silently shifted, and took historiography with it.

* * * * * *

Following Darwin, all the philosophical time-frames of the ancien regime – cyclical time, Platonic time, Absolute time, dialectical time, and the still-existing remnants of the ‘Great Chain of Being’ – were being put to the question. Evolutionism had opened up the deep past of human pre-history, and by the end of the nineteenth century, temporality was all the rage. An early evolutionary biology of inherited characteristics had been put forward called ‘organic memory’ – also known at the time as ‘mneme-theory’ – in which Ernst Haeckel, and others, famously suggested that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ – ie. that each individual is the organic summation of the whole of human history, passing through each historical stage as he or she develops to biological maturity (which Norbert Elias later incorporated into his concept of the civilising process – also unattributed.) By the 1890s the theory of organic memory had acquired a fixed linear teleology of long-term human progress and racial hierarchy (eugenics), the main protagonist of which was ‘Social Darwinist’ Herbert Spencer.

It was partly to oppose the biological determinism of Spencer that Henri Bergson wrote Matiere et Memoir in 1896, Creative Evolution in 1907, and Time and Free Will in 1910. Bergsonianism appears to be a hidden episode, a black hole, in late nineteenth/early twentieth century history. Bergson has been recently resurrected by a new generation of philosophers, but his social impact is highly underestimated. He had a particularly profound creative influence on early 20th cent European writers, poets, and artists – notably the Surrealists. (Sadly I was not able to get an image of Dali’s companion-picture, ‘Perceptions of Time’, which I also saw recently at an exhibition, hung side by side with the above ‘Perceptions of Memory’. ) Bergson’s intimate and poetic lectures drew thousands throughout Europe; he was also a public sensation in his lecture tours of South and North America, where his free-will philosophy was especially strongly appreciated. As the American historian/philosopher Arthur O. Lovejoy commented: ‘an amazingly large part [of the world] is reading him, and apparently the greater part is writing articles about him… It is, in short, a condition as well as a theory which confronts us when we consider the philosophy of Bergson – a condition of the mind of our generation.’

Briefly, Bergsonianism seemed to liberate the individual from the burden of history. For Bergson only the present moment (la duree, or ‘the duration’) was alive and perceptible; but it was also inchoate and unknowable; all previous moments were only recalled as a mechanical ordering of ‘virtual’ events, in space, via memory. Time itself was thus a state of continuous flux, operating at innumerable different levels of consciousness and organisation. Therefore human bodies could never be explained with any reference to the preceding instant, but were subject to a process of ‘unceasing creation’. (B Russell; G Deleuze; J. Mullarky; Grogin, p 77-8) Almost inevitably, this Bergsonian deconstruction of linear time allowed the imagination to play freely with the idea of Time split into different fragments or dimensions, while at the same time celebrating human/animal intuition, instinct, or existential free will. It was evidently highly intriguing; Lovejoy thought that ‘temporalism’, as he called it – ‘ a new thing but a growing thing’ – was Bergson’s outstanding contribution to philosophy. [ADD pic of multiple superimposed images of Lovejoy – his ‘Bergsonian moment’. Thanks to Simon Schaffer. ] Eventually it led to an unresolved debate over whether there was ‘one or many durations’ of time, during which Bergson refuted Einstein’s view of relative time-and-space, and insisted there was only one single, universal flow of physical Time – in this ‘monism’, as in other respects, he was very faithful to Kant, and to transcendental naturphilosophie.

His intellectual and public reputation was huge between 1907 and 1914, but sank in the 1920s and 30s. Between 1905-1915 Einstein slowly but inexorably put forward the special theory of relativity, and Bergson’s vitalist philosophy was firmly trounced by Einstein’s physical science; as Einstein put it – ‘There is no ‘philosopher’s time’. In a public debate with Einstein on relative time Bergson spoke for over an hour; Einstein spoke for six minutes. He then got up, walked out, and took most of the audience with him.

In the strongly materialist French Academy Bergson was considered a political conservative and reviled later as a Catholic convert, as well as for the overtly ‘irrational’ or spiritual aspects of his philosophy, which were also distasteful to Anglo-Saxon empirical philosophers of logical analysis like Russell and Wittgenstein. This was undoubtedly why the equally strongly materialist Annales historians did not nail their colours to his flag, and allowed his reputation to lapse. It is even more the case today, when his descriptions of the physiology of ‘datum-gathering,’ or free-will ‘elan vital’, grate uncomfortably with the findings of modern genetics and brain anatomy. But he left the legacy of a philosophical terminology which the Annalistes internalised and developed – the concept of the duree (short and long), the analysis of multi-facetted memory (external and internal memory), and the idea of a multi-dimensional historical process consisting of constant change and adaptation. As oral historian Bill Schwarz put it his essay in the recent series ‘Regimes of Memory’: ‘So long as the underlying dynamic of history was theorised as singular – civilisation, reason, the spirit of the nation, climate, the people, class – then historical time was necessarily singular too…only in the 20th century can we properly begin to identify the emergence of a contrary, plural conception of historical time.’ (B S p 137). Incidentally, this sophisticated historian takes the 1950s Braudel as his starting point and model for up-to-date post-structuralism; so much for the historiographical longue duree.

* * * * *

Conclusions…?

- The tendency to retain a nineteenth-century ‘one-dimensional’ view of time is particularly noticeable in the work of social scientists. And this is despite the fact that there is now a growing sociology of time; and a new geography of time and space; and that in health studies, time is now increasingly recognised as a factor in clinical therapeutics, and service delivery. (N.B. Barbara Adam; R. Frankenberg ed; Carlsten, Parkes & Thrift eds, Timing Space and Spacing Time, 1978). But there is still the distinct danger that the various and numerous micro-temporal studies of bodily activities, will simply be ‘tacked on’ to other statistical factors, ignoring the existence of multi-dimensional time, with all of its different ‘durations’. The ‘health behaviouralism’ of the social sciences is often static, frozen in time. In health development work, the so-called ‘ethnic’ and ‘western’ medical systems are often treated as separate, and oppositional (dualist), monoliths, rather than simultaneous layers of cultural experience. There is little idea of historical process (other than 20th – 21st century progress) in the world of practical science; perhaps more than any other social group, they are strongly future-orientated.

- Then there is cultural history. As we know, even social and cultural historians often struggle to interpret their temporal evidence with any degree of confidence, or indeed with any reference to time outside ‘their’ period. This comfortable refuge in micro-history encourages short-term thinking, and eventually narrows the discipline. In particular, I am thinking of the gulf between historians of the ancient and modern world, and the loss of ancient and prehistory subjects to the teaching curriculum.

If nothing else, the concept of the longue duree demonstrates how ridiculously small a period human history occupies – relatively speaking. From the Annales /Bergsonian view-point, modern historians will always need longue duree history to lay down the geo-socio-economic substrata of matter and memory. Ancient historians are less exclusive – they have already taken on board the need for the modern structural models of anthropology and sociology, to help breathe process and meaning into their archaeology. And if even the popular media acknowledges history as a palimpsest – ‘what the Romans did for us etc’ – where is the debate from the historians?

Time-theory also suggests that there are incipient problems with world history, or post-colonial history as it is too often called – the name ‘post-colonial’ is so obviously ‘linear’ and one-dimensional. The world’s continents display all the evidence of simultaneous multi-cultural development, not least with ancient histories which were and are (as everybody has so recently discovered) so obviously alive and kicking. As historians, we need always ask first, and recognise, the basic temporal questions.

© Virginia Smith

July 2007